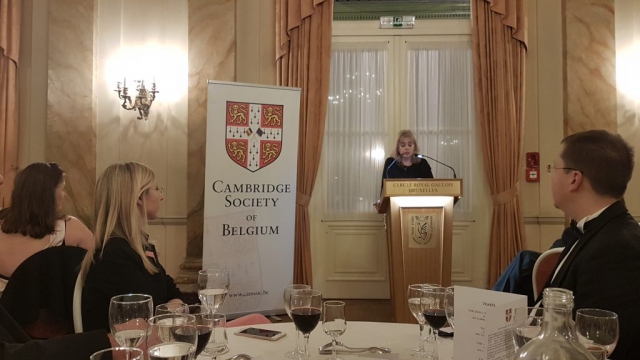

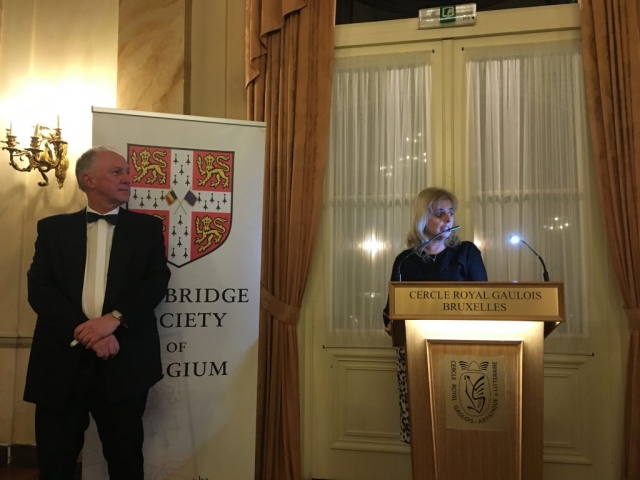

We had a wonderful evening at the Cercle Royale Gaulois. Our Guest of honour, Prof Catharine Barnard, gave an impressive speech which was frequently interrupted by applause and completed by a standing ovation! Her talk was followed by many interesting comments, questions and answers. Several members commented on the great ambiance.

The Society was extremely pleased by the turnout of not only the more senior members but many many new fresh faces. Catherine has graciously provided us with a written copy of her speech which is provided below. If you do pass this on, do be sure to attribute it to her and our event. Catherine also provided us with the following link to Ivan Rogers’ lecture: https://www.trin.cam.ac.uk/events/brexit-as-a-revolution/ given at Trinity in October 2018.

We would like to thank Catherine, le Cercle Gaulois and all the Cantab Team that made our 25th Anniversary Dinner such a great success.

The Future of Europe

The speech by Professor Catherine Barnard at the occasion of the 25th Anniversary Dinner of the Founding of the Cambridge Society of Belgium.

I am very grateful for this generous invitation to speak at your 25th anniversary. I am very pleased to be here, to meet so many of you, and I am very grateful for the warm welcome. Thank you all.

I have been asked to talk about the future of Europe. You might find this something of an indigestible topic after the glories of Belgian cuisine. For those of you who value the integrity of your digestive system, you may want to mentally switch off. For those of you who can bear it, I trust you will understand that at this point, from our nation’s perspective, this will not necessarily be a joyous and celebratory talk.

So to the Future of Europe.

As a British national living in the UK and living – just about – through the excruciating Brexit process, my concept of the future extends little beyond 29th March, possibly not even beyond 14th February, the next crucial day at Westminster in the tortuous Brexit process.

Safe on this side of the Channel, you may look on with dismay, possibly disdain, at what is going on in your former home country. I understand a number of you now have a European nationality. But Brexit is not simply a problem for those living in the UK. Brexit will cast a long shadow over the future of Europe. Like Banquo’s ghost, it will haunt the present and the future. It may be that the EU will be able to slough the skin of Brexit – or at least pretend it can. But some of the deep causes of Brexit continue to be the spectre at the feast of any relaunch of Europe. I will come to this in a moment. I want to start with a few reflections on Brexit.

Brexit was caused by dissatisfaction. The EU was seen to be serving the interests of the elite, the haves, not the have-nots, the citizens of nowhere not the citizens of somewhere. In fact it was as much a rejection of Westminster as Brussels. But the referendum didn’t offer that option on the ballot paper. The genius of the leave campaign was that it harnessed deep dissatisfaction with the failures of Westminster through the vehicle of the EU referendum. The EU became the cypher, the proxy for dissatisfaction. The very haves, the very citizens of nowhere – the Rees-Moggs, Boris Johnsons, Michael Goves were – extraordinarily – able to pass themselves off as defenders of the poor and disadvantaged to further their own agenda of leaving the big state and replacing it with the small. And, like snake oil salesmen, they were able to pass off new lamps for old. Leave meant all things to all men and women – and that legacy is being felt today and will continue to be felt for decades to come.

Meanwhile Brexit is sucking all of the oxygen out of the system; the capacity for the civil service to do anything apart from prepare for Brexit and prepare for a no deal Brexit is almost non-existent. Just think how that energy – and money – could be better used to deliver improved public services, better schools, a well-funded health service, a social care system to look after the elderly and vulnerable. In short, to right those wrongs that many had voted against.

And the resentment grows. Brexit has not delivered the liberation many had expected and is unlikely to do so unless there is a chaotic no deal Brexit on 29th March. Falling back on WTO terms will not be the salvation many expect. No major trading nation trades solely on WTO terms. The US has over 100 separate side agreements with the EU. The moment there are queues at Dover – with medicine shortages and fresh food disappearing from supermarket shelves, panic, not the Dunkirk spirit, will set in. If the UK has not signed up to the Withdrawal Agreement before, I imagine the PM will be heading speedily to Brussels with her cheque book at the ready and a pen poised to sign.

And that takes us to the transition/implementation period. The UK will be bound by EU law over which it will have no input and will be subject to rulings of the Court of Justice without a British judge.

The politics here will be deeply unstable. Just wait until there is a new piece of legislation which catches the tabloids’ imagination – on flushable loos, the noise of lawnmowers, the brightness of lightbulbs – it is difficult to tell. The tabloids will go bananas. Literally.

And that’s not the last of it. The transition period might be extended to December 2022. The new deal might not be agreed until 2024 or 2025 – trade deals take about 5 years. And that would bring about, you guessed it, the Irish backstop. And let’s just think what that means for the UK. This is where the swimming pool analogy fits in. While Northern Ireland will stay in the Customs Union and the Single Market for goods, GB will stay in the CU. Just think about the practicalities of this. New computer systems for the GB and Northern Irish governments – and we know how good the UK is at procuring IT – significant adaptations for logistics companies – and a border down the Irish sea. The politics of this are poisonous.

So there will be huge pressure on the UK negotiators to reach a deal with the EU quickly to avoid this scenario. As, with Article 50, time is on the EU’s side. It can just sit and wait while the UK finally (?) makes up its mind as to what it wants – stay in the Customs Union with more frictionless trade in goods but no independent trade policy for the UK, or leave the CU and the UK gains its ability to have a trade policy but have friction at the border (and NI will have to stay in the CU and SM for goods to avoid a hard border) – and then negotiate. And the longer it takes, the more concessions the UK will have to make – on financial contribution, on fish, even on free movement.

And the narrative will be one of betrayal, over and over again. British politics is no longer divided on right/left lines but remain/leave. Remainers will be totally disenchanted. They have lost and lost again. They have not been listened to. They have been abused and insulted. There are 16 million of them and their ranks are swelling as more young people become able to vote.

But crucially, Leavers too will be bitter. This is not the pure Brexit they had apparently been promised. As Ivan Rogers said in his Trinity lecture, the Brexit revolution is starting to “eat its own children”. In fact, as we saw, it was never clear what a Brexit vote had actually meant. It was a vote against things, not in favour. A hard Brexiter is likely to be Prime Minister in whose interests it will be to make a case – again and again – against the EU. The blame narrative and the victim mentality will permeate British politics for a generation.

Future of Europe

So what has all of this got to do with the future of Europe? Everything and nothing. From an EU perspective, Brexit has been a triumph of EU diplomacy. The EU 27 have remained extraordinarily united (it is easy to be united against a common enemy, especially one which has demonstrated such arrogance, nay hubris, over the years.) They have called the shots, dictated the timetable. Martin Selmayr must be rubbing his hands with glee.

And yet, for those who think more, they might have their moments of doubt in the middle of the night. Have they pushed the UK too far? Is it really a good idea to have an unreliable partner on their western flank, a partner so closely tied up with an EU Member State (Ireland), not least when there is a cantankerous bear on their Eastern flank. Is it really sensible to antagonise Western Europe’s largest military power, on whom the European states have been so reliant for defence?

And what message does it send out to the people of smaller EU states which have a difficult relationship with the EU? If the EU can behave like this to a big state like the UK, what might it do to a smaller state? Yes, I know there has never been so much pro-EU sentiment. The EU’s short term policy has been successful in ‘decourager les autres’ but is this really the most sensible response?

And what message does it send out to the people of smaller EU states which have a difficult relationship with the EU? If the EU can behave like this to a big state like the UK, what might it do to a smaller state? Yes, I know there has never been so much pro-EU sentiment. The EU’s short term policy has been successful in ‘decourager les autres’ but is this really the most sensible response?

And the problems facing the EU are profound. The EU’s technocratic – Monnet style – response to global problems is so – well last century. Multilateralism is no longer the order of the day. Transnational institutions are increasingly regarded as the enemies of the people, not their protectors. They are seen as remote, unaccountable. They are also seen as, paradoxically, both impotent in the face of day to day problems and omnipotent in respect of all other matters. And they are staffed by those elite, citizens of nowhere.

The EU’s very success has become its Achilles heel. As the European Parliament elections will show, it is facing a crisis of legitimacy and ultimately democracy. The delicate system of checks and balances simply is not working.

The challenge for the EU is to harness both big government and small. Subsidiarity, while appealing, to lawyers, is not the solution. The EU public cannot rally round the word subsidiarity. You can’t see EU citizens rallying to the cry of ‘What, do we want? We want subsidiarity, when do we want it? Now.’

The Committee of the Regions and Economic Social Committee, while admirable, are also not the answer. On paper they look like a sensible response. But in fact, they are camel – a horse designed by a committee – even the committee of the regions.

Money – dispersed through the EIB and through regional funds – might help. It has certainly helped to keep Poland and Hungary on board, at least in respect of managing Brexit. But as Leave voting Cornwall has shown, money does not buy love.

So what can be done? It is easy to say what cannot work but much less easy to say what can.

On a positive note, one of the things that Brexit has revealed, certainly to the UK and perhaps to the EU, is just how successful and how integrated a number of its low profile but crucial policies actually are. For all the talk of bendy bananas, the EU in fact excels at dealing with technocratic areas of government – public procurement, European trading Scheme, single skies, single energy market – those very things for which it is currently most reviled. Effective communication, civic education would all help. The EU tries but the messaging feels clunky and wrong.

But I also wonder whether the EU needs to think more roundly and more wisely. As a parent of teenagers I am often reminded of the fact that they need to be given some freedom. Holding them close, disciplining them like young children no longer works (and they are bigger and stronger than me so it definitely will not work). So should the EU not see a degree of freedom for states as a threat but as a necessity. States going through teenage spasms of independence might benefit from some diversity, not the straightjacket of uniformity and compliance. Should the EU be thinking about allowing greater independence to some of its teenage, awkward states. Should there be greater federalisation? Should there be a Europe of concentric circles. Is this in fact the future?

And this brings me back to Brexit. Should the EU have acted as the grown up in the room? Instead of self-congratulation, should the EU, in fact, have been planning for some sort of EFTA-style holding pattern into which the UK could slip? Isn’t that what parents do – provide some sort of safety net to catch their teenagers when they fall?

In fact, this seems to be too late, at least for the UK. The way things are heading is for the UK to be allowed to fall and for the rest of the EU to feel proud of its ‘I told you so moment’. I wish I could be more optimistic. But I am not. And universities like Cambridge need your support more than ever through these very difficult times.

May I wish you all the best for your 25th anniversary.